I was part of a debate on Tuesday that involved a larger disagreement than any exhibited at the Democratic presidential candidates debate that evening. A group of peace activists met with the president, a board member, some vice presidents, and a senior fellow of the so-called U.S. Institute of Peace, a U.S. government institution that spends tens of millions of public dollars every year on things tangentially related to peace (including promoting wars) but has yet to oppose a single U.S. war in its 30-year history.

I was part of a debate on Tuesday that involved a larger disagreement than any exhibited at the Democratic presidential candidates debate that evening. A group of peace activists met with the president, a board member, some vice presidents, and a senior fellow of the so-called U.S. Institute of Peace, a U.S. government institution that spends tens of millions of public dollars every year on things tangentially related to peace (including promoting wars) but has yet to oppose a single U.S. war in its 30-year history.

Without CNN’s Anderson Cooper there to steer us away from the issues into name calling and triviality, we dove right into the substance. The gap between the culture of peace activists and that of the U.S. Institute of “Peace” (USIP) is immense.

We had created and took the occasion to deliver a petition which you should sign if you haven’t, urging USIP to remove from its board prominent war mongers and members of the boards of weapons companies. The petition also recommends numerous ideas for useful projects USIP could work on. I blogged about this earlier here and here.

We showed up Tuesday at USIP’s fancy new building next to the Lincoln Memorial. Carved in the marble are the names of USIP’s sponsors, from Lockheed Martin on down through many of the major weapons and oil corporations.

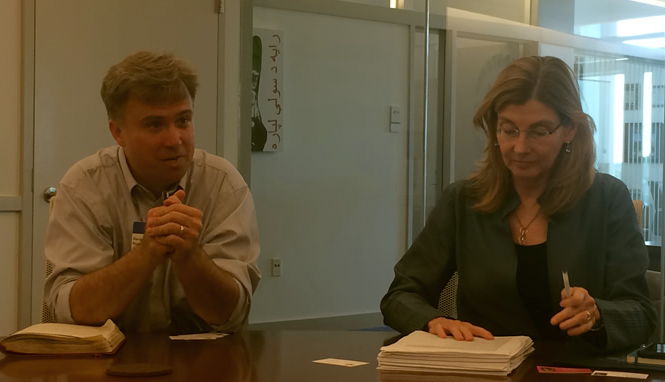

At the meeting from the peace movement were Medea Benjamin, Kevin Zeese, Michaela Anang, Alli McCracken, and me. Representing USIP were President Nancy Lindborg, Acting Vice President Middle East and Africa Center Manal Omar, Director of Peace Funders Collaborative Steve Riskin, Board Member Joseph Eldridge, and Senior Policy Fellow Maria Stephan. They took 90 minutes or so to talk with us but seemed to have no interest in meeting any of our requests.

They claimed the Board was no impediment to anything they wanted to do, so there was no point in changing board members. They claimed to have already done some of the projects we proposed (and we look forward to seeing those details), yet they were uninterested in pursuing any of them.

When we proposed that they advocate against U.S. militarism in any number of possible ways, they replied with a couple of main justifications for not doing so. First, they claimed that if they did anything that displeased Congress, their funding would dry up. That’s likely true. Second, they claimed they could not advocate for or against anything at all. But that isn’t true. They’ve advocated for a no-fly zone in Syria, regime change in Syria, arming and training killers in Iraq and Syria, and (more peacefully) for upholding the nuclear agreement with Iran. They testify before Congress and in the media all the time, advocating for things left and right. I don’t care if they call such activities something other than advocacy, I’d just like to see them do more of what they’ve done on Iran and less of what they’ve done on Syria. And by law they are perfectly free to advocate even on legislation as long as a member of Congress asks them to.

When I had first communicated about our petition with USIP they had expressed interest in possibly working on one or more of the projects we proposed, possibly including reports we suggest in the petition that they write. When I asked about those report ideas on Tuesday, the reply was that they just didn’t have the staff. They have hundreds of staff, they said, but they’re all busy. They’ve made thousands of grants, they said, but couldn’t make one for anything like that.

What may help explain the array of excuses we were offered is another factor I haven’t yet touched on. USIP seems to actually believe in war. The president of USIP Nancy Lindborg had an odd response when I suggested that inviting Senator Tom Cotton to come speak at USIP on the need for a longer war on Afghanistan was a problem. She said USIP had to please Congress. OK, fine. Then she added that she believed there was room to disagree about exactly how we were going to make peace in Afghanistan, that there was more than one possible path to peace. Of course I didn’t think “we” were going to make peace in Afghanistan, I wanted “us” to get out of there and allow Afghans to start working on that problem. But I asked Lindborg if one of her possible paths to peace was through war. She asked me to define war. I said that war was the use of the U.S. military to kill people. She said that “non-combat troops” could be the answer. (I note that for all their non-combatting, people still just burned to death in a hospital.)

Syria brought out a similar perspective. While Lindborg claimed that USIP’s promotion of war on Syria had all been the unofficial work of one staffer, she described the war in Syria in a completely one-sided manner and asked what could be done about a brutal dictator like Assad killing people with “barrel bombs”, lamenting the lack of “action”. She believed the hospital bombing in Afghanistan would make President Obama even more reluctant to use force. (If this is reluctance, I’d hate to see eagerness!)

So what does USIP do if it doesn’t do war opposition? If it won’t oppose military spending? If it won’t encourage transition to peaceful industries? If there’s nothing it will risk its funding for, what is the good work it is protecting? Lindborg said that USIP spent its first decade creating the field of peace studies by developing the curriculum for it. I’m pretty sure that’s a bit anachronistic and exaggerated, but it would help explain the lack of war opposition in peace studies programs.

Since then, USIP has worked on the sorts of things taught in peace studies programs by funding groups on the ground in troubled countries. Somehow the troubled countries that get the greatest attention tend to be those like Syria that the U.S. government wants to overthrow, rather than those like Bahrain that the U.S. government wants to prop up. Still, there is plenty of good work funded. It’s just work that doesn’t too directly oppose U.S. militarism. And because the U.S. is the top arms supplier to the world and the top investor in and user of war in the world, and because it’s impossible to build peace under U.S. bombs, this work is severely limited.

The constraints that USIP is under or believes it is under or doesn’t mind being under (and enthusiasts for creating a “Department of Peace” should pay attention) are those created by a corrupt and militaristic Congress and White House. USIP openly said in our meeting that the root problem is corrupt elections. But when some section of the government does something less militaristic than some other section, such as negotiating the agreement with Iran, USIP can play a role. So our role, perhaps, is to nudge them toward playing that role as much as possible, as well as away from such outrages as promoting war in Syria (which it sounds like they may leave largely to their board members now).

When we discussed USIP’s board members and got nowhere, we suggested an advisory board that could include peace activists. That went nowhere. So we suggested that they create a liaison to the peace movement. USIP liked that idea. So, be prepared to liaise with the Institute. Please start by signing the petition.